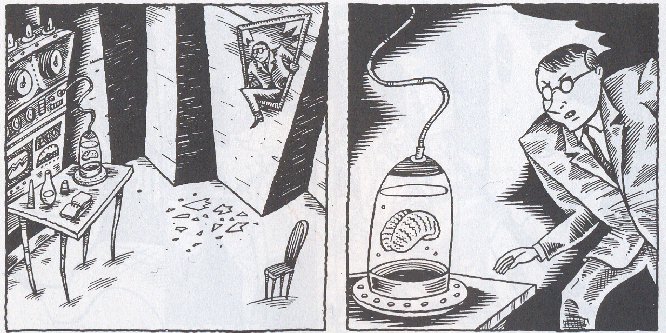

“the highly unnatural laboratory environment

invariably stresses the animals, and stress affects the entire organism by

altering pulse, blood pressure, hormone levels, immunological activities and a

myriad of other functions. Indeed, many laboratory "discoveries"

reflect mere laboratory artefact”

|

| An intense mouse. Can an artificial environment affect the physiology of an animal in such a way that it bears on medical and other research? |

The rough idea is that

the artificial laboratory conditions may affect the results of experiments in

important ways.

Scientists researching social cognition in chimpanzees,

say, need to be aware that a laboratory environment may affect the animal’s

normal psychology. For example, long time interaction with humans may make an animal more susceptible to certain human oriented behaviour, another factor

which might affect generalisation from results. Experiments

involving tasks in which chimps must assist humans need to take into account whether the subjects

have prior history with experimenters. And indeed this is discussed and taken

into account in many good experiments.

There is nothing necessarily wrong with experiments into social cognition in chimps within a

laboratory setting. It would be foolish of us to disregard all laboratory based research. In most cases it is the only possible environment.

In one of my favourite studies, designed explicitly to compare human infants and young chimpanzee altruistic tendencies, human and infant chimps were tested on similar tasks (Warneken and Tomasello, 2006: 1). A human experimenter confronted a problem and needed assistance (e.g. reaching for an out-of-reach-marker, bumping into object that needs removal), with no reward given for help. Whilst the human infant intervened in more tasks than the chimp, the latter did reliably assist in the tasks involving reaching (incidentally also the task in which the children most reliably helped). These results, I believe, provide good support for a natural capacity, in both human and chimps, for non-selfish helping behaviour and tendencies beyond near kin, . It is hard to fault this study for taking place in laboratory settings.

In one of my favourite studies, designed explicitly to compare human infants and young chimpanzee altruistic tendencies, human and infant chimps were tested on similar tasks (Warneken and Tomasello, 2006: 1). A human experimenter confronted a problem and needed assistance (e.g. reaching for an out-of-reach-marker, bumping into object that needs removal), with no reward given for help. Whilst the human infant intervened in more tasks than the chimp, the latter did reliably assist in the tasks involving reaching (incidentally also the task in which the children most reliably helped). These results, I believe, provide good support for a natural capacity, in both human and chimps, for non-selfish helping behaviour and tendencies beyond near kin, . It is hard to fault this study for taking place in laboratory settings.

|

| In addition to possessing theory of mind, this guy can actually possess your mind. |

Nevertheless the setting and

history of all subjects must be taken into account as a potentially relevant

variable. In short we need be aware of the possibility that a laboratory

setting might affect the psychology and thus behaviour of animal subjects.

Warneken F, Hare B, Melis AP, Hanus D, Tomasello M (2007) Spontaneous Altruism by Chimpanzees and Young Children. PLoS Biol 5(7): e184. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050184