My thoughts on this were prompted by reading Noë (2007), who spends some time discussing the hypothetical isolation of a brain, and what, if anything, it would experience. This is in the context of the search for a neural correlate for consciousness (NCC), a region (or regions) of the brain that is sufficient for conscious experience. Neuroscience is often implicitly committed to the existence of a NCC, and several philosophers are explicitly committed to it, advocating what Noë terms the Neural Substrate Thesis: "for every experience there is a neural process [...] whose activation suffices for the experience" (ibid: 1). If the Neural Substrate Thesis (NST) is correct, then neuroscience will eventually discover a NCC.

Noë focuses on two philosophers who advocate the NST, Ned Block and John Searle. Conveniently, both Block and Searle have also made important contributions to the corpus of philosophical thought experiments. Noë's main point is that focusing exclusively on the brain as the seat of consciousness can in fact be very counterintuitive, to the point of rendering some thought experiments almost incoherent. He demonstrates this with a discussion of the following "duplication scenario" (Noë 2007: 11-15), at least inspired by (if not attributed to), Block:

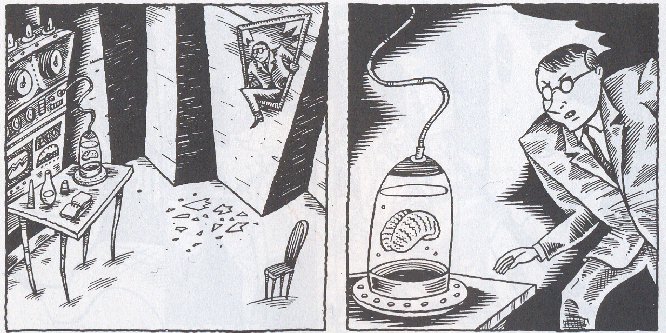

We are asked to imagine that my brain has an exact duplicate, a twin-brain that, if NST is correct, will undergo the exact same conscious experience that I do. Furthermore, if NST is correct, then provided that this brain continues to mimic my own, it doesn't matter what environment we place it in. It might enjoy an identical situation to my brain, or it might be stimulated just so by an expert neurosurgeon, or it might even be dangling in space, maintained and supported by a miraculous coincidence (see Schwitzgebel's discussion of the disembodied "Boltzmann Brain"). In the first couple of cases, Noë agrees that my twin-brain might well be conscious, but only by virtue of its environment (2007: 13). The final case, what he calls a "disembodied, dangling, accidental brain" (ibid: 15), seems to him to be verging on the unintelligible, and I can see his point. At the very least, it is surely an empirical question whether or not such a brain would be conscious, and one that we have no obvious way of answering.

I'm not really sure what's going on here.

Similar reasoning can be applied to Searle's Chinese Room thought experiment. Clearly the man inside the room doesn't understand Chinese, but that's not the point. The extended cognitive system that is composed of the man, his books, and the room, does seem to understand Chinese. It may even be worthy of being called conscious, although I suspect that the glacial speed at which it functions probably hinders this.

Back to Block. He has argued against functionalism with his China Brain thought experiment. My instinct is that, contra Block, the cognitive system formed by neurone-radios might well be conscious, although the speed at which it operated would give it a unique perspective. Furthermore, it might only be conscious if it were correctly situated, perhaps connected to a human-sized robot or body, as in the original experiment. The pseudo-neuronal system is not enough - it would require the correct kind of embodiment and environmental input to function adequately.

In fact, embodiment concerns might undermine a more radical version of the China Brain proposed by Eric Schwitzgebel. Schwitzgebel argues that complex nation-states such as the USA and China are in fact conscious, due to their functional similarity to conscious cognitive systems. I'm sympathetic to his arguments, but my concern is that such a "nation-brain" might not, in practice, be properly embodied. Aside from structural and temporal issues, it would lack a body with which to interact with the environment, and at best it might enjoy a radically different form of consciousness to our own. Even if it were conscious, we could have difficulty identifying that it was.2 So embodiment is a , double-edged sword - it doesn't always support the most radical philosophical conclusions, and it can sometimes end reinforcing more traditional positions.

1. Literally a few minutes after writing this I realised that Clark (2009: 980-1) makes a very similar point!

2. This is somewhat reminiscent of Wittgenstein's claim that "If a lion could talk, we wouldn't be able to understand it." (1953/2009: #327)

- Clark, A. 2009. "Spreading the Joy? Why the Machinery of Consciousness is (Probably) Still in the Head." Mind 118: 963-993.

- Noë, A. 2007. "Magic Realism and the Limits of Intelligibility: What Makes Us Conscious?" Retrieved from http://ist-socrates.berkeley.edu/~noe/magic.pdf

- Wittgenstein, L. 1953/2009. Philosophical Investigations. Wiley-Blackwell.